Remember, Remember: The Evolution of Guy Fawkes Night

Every year on November 5, the skies of Britain blaze with fireworks, leaving traces of a distinctly British sense of spectacle, satire, and troubling religious turmoil. But behind this beloved spectacle lies a story of division, rebellion, torture, and transformation, one that has stretched from the reign of Elizabeth I to the era of Anonymous and Occupy Wall Street.

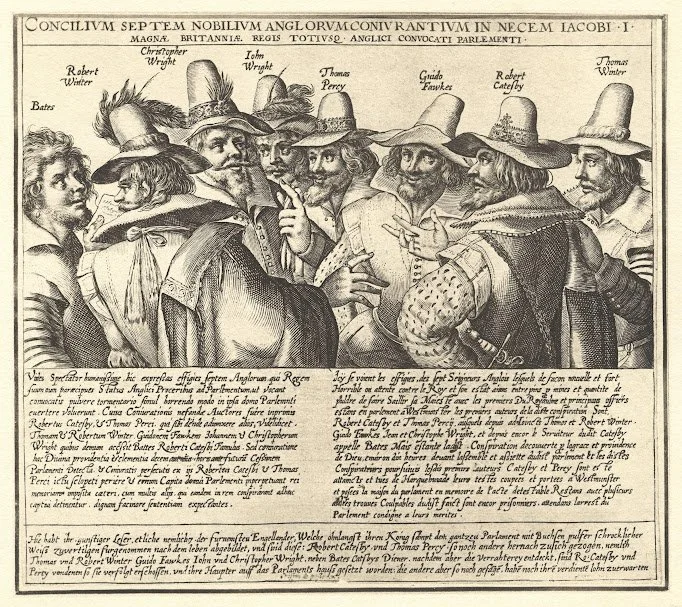

The Gunpowder Plot Conspirators, 1605, by Crispijn de Passe the Elder, National Portrait Gallery

From Faith to Fire

After the Protestant Reformation, Catholics in England faced fines, imprisonment, and persecution for refusing to attend the Church of England’s services. Hopes for tolerance rose when James VI of Scotland became James I of England in 1603, only to be dashed when his policies continued to exclude Catholics.

Out of this frustration grew the Gunpowder Plot of 1605: a plan by ringleader Robert Catesby, Guy Fawkes (known as Guido), and other conspirators to blow up Parliament and restore Catholic influence. The plot unraveled when Fawkes was discovered guarding 36 barrels of gunpowder in a cellar the conspirators had leased beneath the House of Lords.

Guy Fawkes' Lantern, Ashmolean Museum

Yet when Fawkes continued to stay silent through questioning by the Privy Council, the King authorized “the gentler tortures first, and then the sterner.”

Fawkes was transferred to the Tower of London, where his treatment escalated over several days. Those gentler methods likely included manacles, shackled wrists, and suspension from the ceiling. When that failed, he was taken to the rack in the Tower’s dungeons. The rack, a wooden frame with rollers at each end, was designed to stretch the body, dislocating shoulders, elbows, hips, and knees until joints and muscles tore.

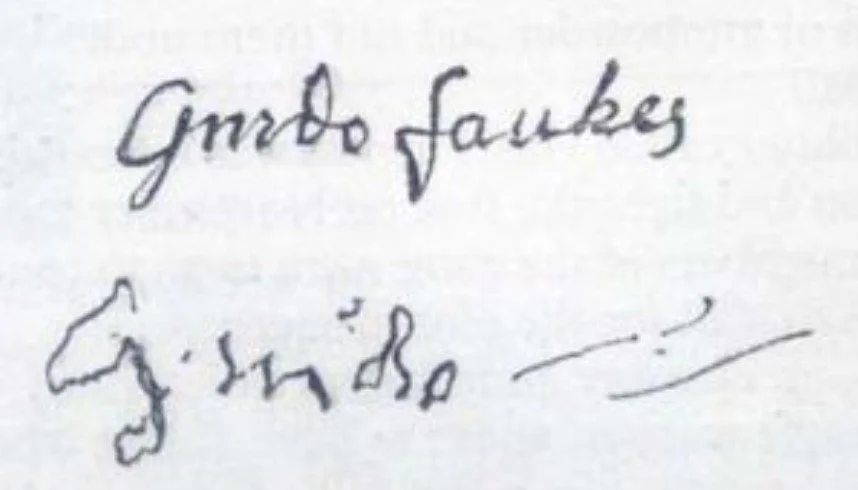

Under these conditions, Fawkes’s endurance finally broke. Over several sessions between 6 and 8 November, he revealed the names of some co-conspirators and confirmed the details of the Gunpowder Plot.

The government’s ultimate aim was to prove a wider Catholic conspiracy in order to reinforce anti-Catholic laws and consolidate James I’s authority.

Two signatures of Guy Fawkes—one firm and legible, the other faint and unsteady—illustrate the effects of torture following his arrest for the Gunpowder Plot of 1605.

The Execution of the Conspirators in the Gunpowder Plot by Claes Jansz Visscher, National Portrait Gallery

The execution took place in Old Palace Yard, directly opposite the Houses of Parliament, the very building the gunpowder plotters had conspired to destroy. Each man was hanged until nearly dead, cut down while still alive, disemboweled (their entrails burned before them), and emasculated (the removal of the genitals), then beheaded and quartered, with body parts displayed publicly as a warning to others.

Fawkes was no fool; he’d endured quite enough. When his moment arrived, he leapt from the gallows ladder, snapping his own neck in the fall. This act spared him the agony of being drawn and quartered alive, a last assertion of control in the face of the crown’s intended humiliation.

Windsor Castle from the Lower Court on the Fifth of November—Fireworks, 1776, by Paul Sandby. The Art Institute of Chicago

Bonfires, Effigies, and the Birth of a Tradition

In 1606, Parliament passed the Thanksgiving Act, mandating annual church services to celebrate the plot’s failure. But the people turned solemn thanksgiving into fiery festivity. Across England, bonfires blazed, bells rang, and effigies of Fawkes and the Pope were burned.

As the centuries passed, the day absorbed older autumn fire customs, blending pagan harvest fires, All Hallows’ rituals, and Protestant pageantry. It became both a patriotic spectacle and a night of licensed mischief.

The Gordon Riots by Charles Green, The Papillon Gallery

Riot and Reform

The 18th century brought volatility. Events like the Gordon Riots of 1780, anti-Catholic uprisings that left hundreds dead, highlighted how combustible religious tensions still were. But by the Victorian era, Bonfire Night had softened. Public displays and children’s traditions replaced riotous mobs.

The Thanksgiving Act was repealed in 1859, ending the state’s role in promoting anti-Catholic observance, and Bonfire Night was reborn as a secular autumn celebration.

“Penny for the Guy”

For generations, anarchic children paraded homemade “Guys” through the streets, asking for “a penny for the Guy.” The coins collected were spent on fireworks, sparklers, sweets, or to help fund the local bonfire where the “Guy” would later be burned.

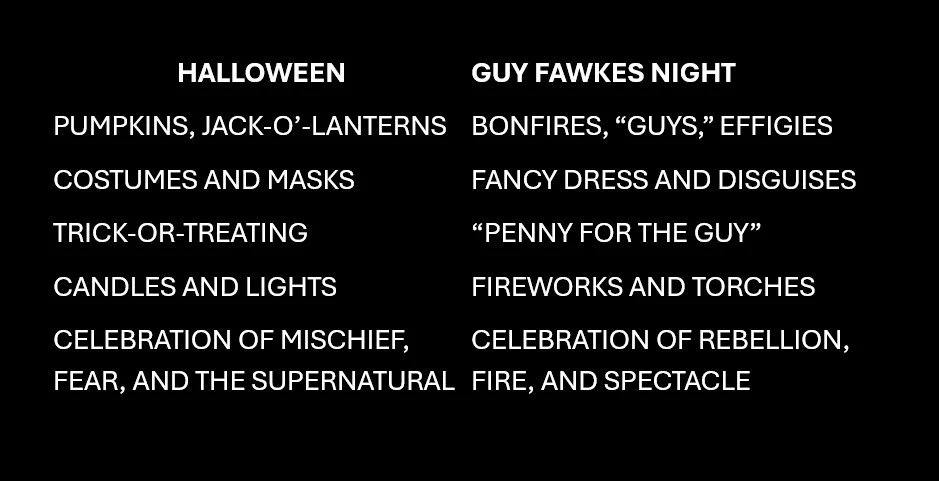

This tradition thrived through the 19th and 20th centuries but faded by the late 20th century, eclipsed by Halloween’s Americanized ascent. Stricter firework and bonfire safety laws from the mid-20th century onward, and the rise of organized public displays, reduced the need for children to raise money to buy fireworks themselves. Inflation and the decline of small coinage made the idea of “a penny” obsolete. Meanwhile, children’s leisure moved indoors, and the old street culture that supported the custom faded.

By the 2000s, Halloween and Bonfire Night had blended into a shared autumn festival season. Both involve fire, costumes, and light against darkness, but the religious and political meanings of November 5 have largely disappeared.

Bonfire Night disorder, BBC

Fireworks, Law, and Safety

Modern concerns are more practical than political: firework injuries, vandalism, and illegal sales. The UK Fireworks Act 2003 restricts sales and sets curfews (usually 11 pm, midnight on November 5). Growing calls for “silent” fireworks aim to protect pets and wildlife.

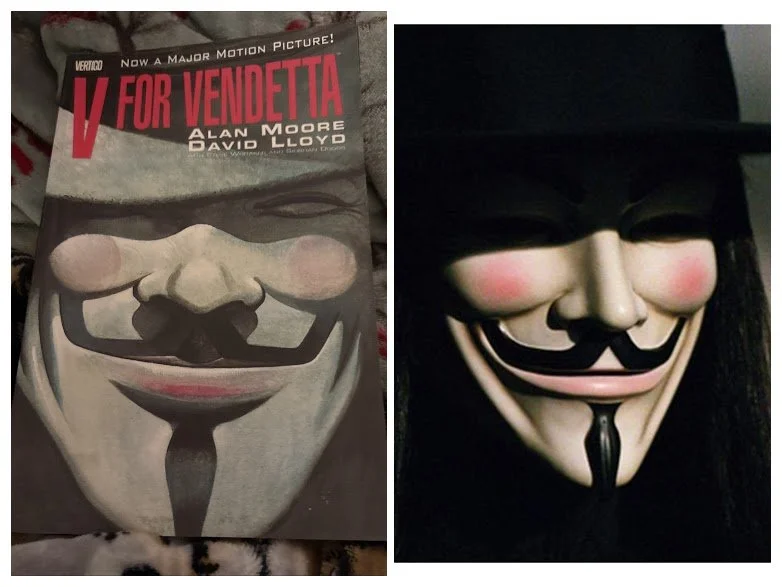

The V for Vendetta graphic novel and its real-world counterpart: the Guy Fawkes mask adopted by global protest movements as a symbol of resistance and anonymity.

From Villain to Icon: V for Vendetta and Anonymous

The late 20th century saw Guy Fawkes reborn again, this time through Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s 1980s graphic novel V for Vendetta and its 2005 film adaptation. Its masked vigilante, “V,” fought tyranny with words and fire, turning the Fawkes mask into a global emblem of rebellion.

Occupy Wall Street in 'Vendetta' masks, CNN

The hacktivist collective Anonymous adopted the mask in the 2000s, using it in data leaks and political demonstrations. It appeared in Occupy Wall Street, WikiLeaks rallies, and was worn by Julian Assange himself. Ironically, the man who tried to blow up Parliament now represents citizens holding power to account.

Liz Truss effigy, Independent

Flames of Satire

In Britain, the town of Lewes in East Sussex hosts the nation’s most spectacular Bonfire Night, featuring torchlit parades and fiery pageantry that recall Protestant martyrs and 17th-century defiance. The event keeps the spirit of satire alive with the burning of effigies of political figures such as Liz Truss, the shortest-serving UK Prime Minister, who held office for just 49 days in 2022. These paper-mâché caricatures blend folk art, humor, and political commentary, continuing a 400-year-old dialogue between authority and the people.

Lewes’s Waterloo Bonfire Society parades through the streets, Photo credit: LFP / Alamy via Discover Britain

Enduring Legacy of Treason and Memory

From a failed 1605 conspiracy to a global icon of protest, Guy Fawkes Night has outgrown its origins. Once a symbol of religious hatred, it is now a secular festival of light and satire. Its negative association with Catholicism continues to transmit a lingering, albeit faint, unease, proof that history’s darkest sparks can ignite new meanings.

A famous rhyme emerged in the 17th century, soon after the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605, as part of England’s official effort to ensure the event was never forgotten. Over time, its words evolved; some versions added or dropped lines, but the opening stanza, like acts of rebellion, remained constant.

“Remember, remember the fifth of November,

Gunpowder, treason and plot…”