The Arms of Washington Heights: Bridges That Reach, Towers That Watch

Washington Heights has long stood as a sentinel at Manhattan’s northern edge, a neighborhood shaped as much by its geography as its towering landmarks. Here, two great bridges extend like steel arms across the Hudson and Harlem Rivers: the George Washington Bridge to the west, a modern marvel completed in 1931, and the High Bridge to the east, New York’s oldest surviving bridge and a relic of 19th-century ambition.

One of the defining forces that shaped Washington Heights—literally and figuratively—was New York City’s 19th-century push for clean, reliable water. In the early 1800s, Lower Manhattan suffered frequent epidemics due to contaminated wells and poor sanitation.

Droves of diseases, including the 1832 cholera epidemic that killed around 3,500 people, wreaked havoc on the overcrowded city.

The solution was ambitious and unprecedented: bring fresh water from upstate via an aqueduct system to the Big—albeit thirsty—Apple.

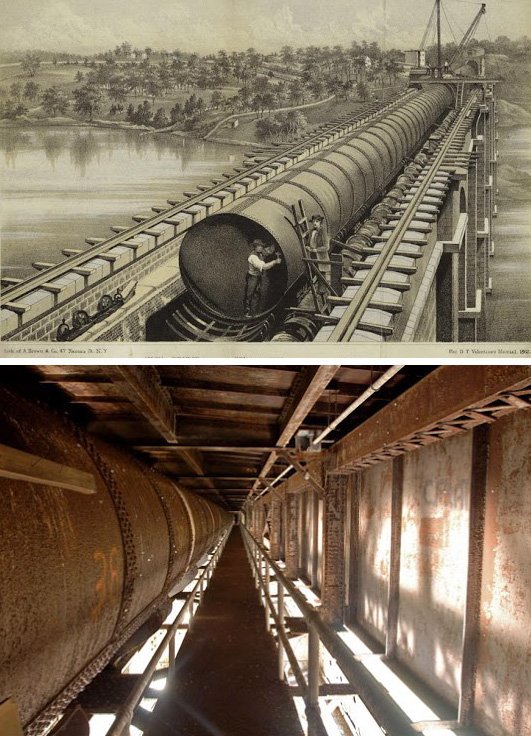

The High Bridge is New York City’s oldest surviving bridge and a remarkable feat of 19th-century engineering. It was built as part of the Croton Aqueduct system, which transported fresh water from the Croton River in Westchester County.

The bridge was designed in the style of a Roman aqueduct, featuring 15 stone arches that spanned the Harlem River. It stood 140 feet above the river and extended over 1,450 feet across. As well as being a lifesaver, the bridge was praised for its classical beauty when it was completed.

As modern plumbing evolved, water stopped flowing over the bridge in the 1950s, and the High Bridge fell into disrepair. Many years later, the bridge was revived and restored. It reopened in 2015 as a pedestrian and cycling path, reconnecting Washington Heights to the Bronx.

Rising 200 feet above Highbridge Park in Washington Heights, the Highbridge Water Tower, constructed from granite ashlar and built between 1866 and 1872, is an octagonal Romanesque Revival structure, designed by John B. Jervis, the chief engineer of the Croton Aqueduct project. The tower held a 47,000-gallon water tank, designed to regulate water pressure and supply water to areas at higher elevations, particularly Washington Heights and Harlem, which sat too high to be served by gravity alone from the Croton system.

Though decommissioned in the 1950s, the tower underwent restoration in the 1980s and the 2020s. Occasionally open for public tours, it offers panoramic views of a part of the city that few tourists ever see.

In the 1930s, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) converted the Highbridge Reservoir into a public swimming pool (Highbridge Pool).

Meanwhile, Highbridge Park, one of the most rugged and naturally wild-feeling green spaces in Manhattan, hugs the eastern bluff of Washington Heights and follows the route of the Old Croton Aqueduct.

Spanning the Hudson River between Washington Heights in Manhattan and Fort Lee, New Jersey, the George Washington Bridge represents a turning point in modern urban mobility and large-scale bridge design. When the bridge opened to traffic in 1931, it boasted the longest main span in the world at 3,500 feet. The bridge serves as a vital connection between New York City, the greater tri-state area, and the Northeast Corridor. With over 100 million vehicles crossing it annually, it is the busiest bridge in the world.

The bridge was designed by Othmar Ammann, a Swiss-born engineer whose bold and elegant solutions would come to define much of New York’s bridge-building in the 20th century. Ammann’s approach prioritized structural clarity and cost efficiency, an ethos well-suited to the challenges of the Great Depression. Originally planned with stone-clad towers in the Beaux-Arts style, the Depression forced a redesign, leaving the steel lattice towers exposed, a choice that unexpectedly gave the bridge its striking modernist aesthetic.

Upon its opening, the George Washington Bridge had an immediate and transformative effect on Washington Heights and the entire northern Manhattan region. Before the bridge, this area was relatively isolated, with limited connections to New Jersey and beyond. The bridge drastically improved access to upper Manhattan, making it a more attractive neighborhood for residential and economic growth.

In 1962, a lower deck was added to accommodate increased traffic, nicknamed “Martha” in reference to George Washington’s wife. At the opening ceremony on August 29th, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller and New Jersey Governor Richard J. Hughes were in attendance. The lower deck addition made the George Washington Bridge the world’s only 14-lane suspension bridge.

Beneath the massive steel span of the George Washington Bridge, tucked along the Hudson River shoreline in Fort Washington Park, stands a small but beloved structure: the Little Red Lighthouse. Officially known as the Jeffrey’s Hook Lighthouse, it was originally constructed in 1880 and first installed at Sandy Hook, New Jersey, where it functioned as a navigational aid at the entrance to New York Harbor.

In 1921, the lighthouse was relocated to its current site at Jeffrey’s Hook, a rocky point on the Hudson River on the west side of Washington Heights, just beneath where the George Washington Bridge would later be built. It was moved there to help guide barge traffic through a tricky and sometimes treacherous bend in the river. Though only 40 feet tall, its bright red cast-iron frame made it a cheerful and practical beacon on the Manhattan shoreline, until progress threatened to render it obsolete.

When the George Washington Bridge was completed in 1931, the lighthouse, now cast in the shadow of the towering, beaming span, no longer served a purpose.

It was decommissioned in 1947, and a few years later, it was destined for demolition.

However, children across the United States began writing letters in protest. They had read The Little Red Lighthouse and the Great Gray Bridge, a popular 1942 picture book by Hildegarde H. Swift, illustrated by Lynd Ward. Its message—“even small things have their place”—deeply resonated with young readers.

In a rare moment of grassroots triumph, this junior power-to-the-people movement ultimately saved the lighthouse.

The Little Red Lighthouse was designated a New York City Landmark in 1991. Today, visitors can gain access through the Historic House Trust of New York City.

It is Manhattan’s only surviving lighthouse.