The Dutch Are Still Here: Tracing Four Centuries of Influence in New York City

1660 map of New Amsterdam superimposed onto a 1900 maps of Manhattan, Mapping New York

Squint your eyes on a walk through Lower Manhattan, and a city the Dutch built will emerge.

As 2025 marks 400 years since New Amsterdam became the capital of New Netherland and 750 years since Amsterdam received its city charter, it’s worth asking: how Dutch is New York still?

Nieu Amsterdam, New York Public Library

A City Born of Trade, Not Doctrine

When the Dutch West India Company planted a fort on the tip of Manhattan in 1625, they weren’t chasing religious utopias or aristocratic estates. They came for fur and trade, and in doing so, built a city structured for commerce, efficiency, and tolerance, at least relative to the standards of 17th-century Europe (and certainly more so than New England).

Who else but the Dutch would convert a pub into New Amsterdam’s first City Hall (Stadt Huys)?

While Puritans in Salem were pointing the witchfinder finger at each other in the 1690s, British expats in Lower Manhattan were luxuriating in a comparatively liberal society originally established by the Dutch.

The first settlers included not only Dutch but also Sephardic Jews, other Europeans, Africans (many enslaved), and Indigenous traders, speaking an estimated 18 languages.

Stepped Gable, Brooklyn

NYC stoops

From the Dutch word "stoep," meaning "step," “sidewalk,” or "porch."

In 2025, New York marks 400 years since New Amsterdam became the capital of New Netherland. The Dutch legacy still shapes the city in surprising ways. Streets like Broad, Pearl, and Wall still follow the original Dutch plan. And while the British took control in 1664, they were so impressed by Dutch governance that much of it remained intact.

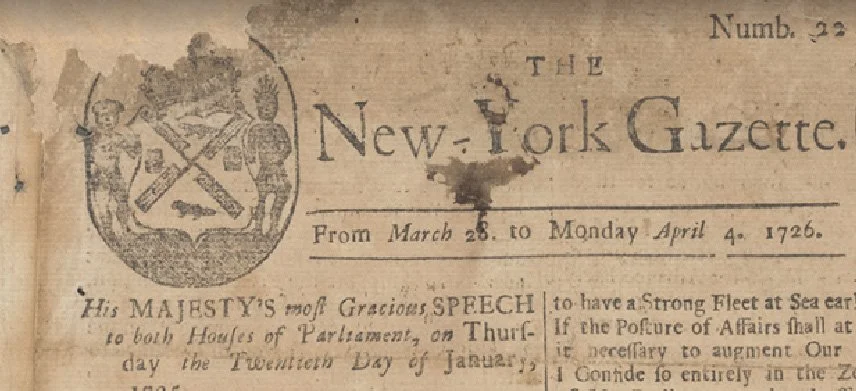

The New York Gazette, 1726

Dutch Words and Dynasties

Dutch still colors New York speech: stoop, cookie, coleslaw, boss. Boroughs and neighborhoods like Harlem, Brooklyn, and Flushing still carry the names (though anglicized) of towns in the Netherlands.

The New-York Gazette, printed by William Bradford (the colony’s first printer), featured early 18th-century Dutch-influenced typography and iconography—including a windmill, Native American, and beaver—tracing directly back to the seal of New Amsterdam, the foundation for today’s New York City seal.

Several of New York’s most enduring families trace their roots to Dutch settlers, including the Roosevelts, Van Cortlandts, Schuylers, Stuyvesants, and Vanderbilts.

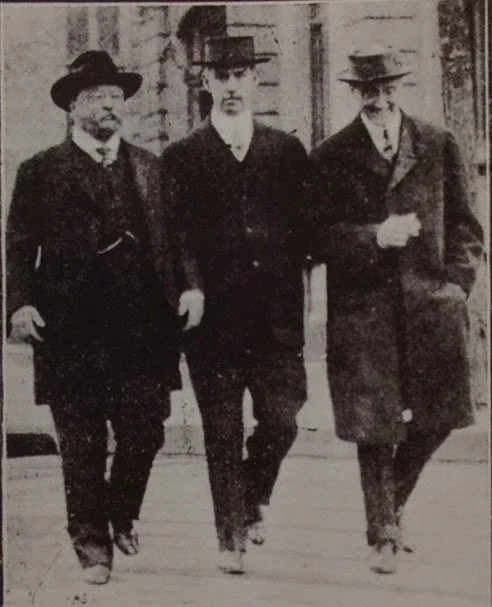

The earliest known photograph of both Theodore Roosevelt (left) and Franklin Delano Roosevelt (right) together, from 1915

The Roosevelts typified Dutch colonial values, such as civic duty and self-reliance, qualities that echoed in their presidencies. Both Theodore and Franklin championed reform, infrastructure, and strong government shaped by moral principle, rooted in the Dutch burgher tradition.

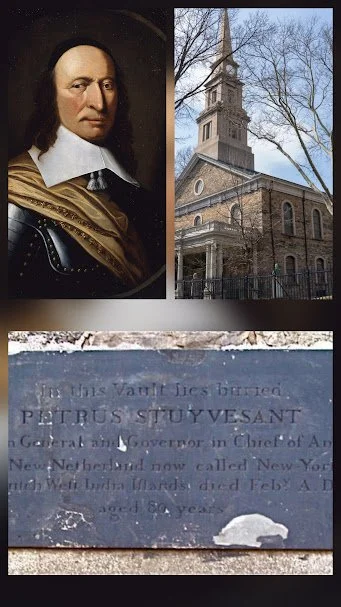

Peter Stuyvesant, the one-legged final governor of New Netherland, is buried beneath St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery. Though regarded as a brilliant colonial administrator, he was widely known for his strict rule and religious intolerance.

Harry F. Sinclair House (now the Ukrainian Institute of America)

His last direct descendants, Augustus Stuyvesant Jr. and his sister Anne van Horne Stuyvesant, lived quietly in their Fifth Avenue mansion, the Harry F. Sinclair House, now home to the Ukrainian Institute of America. Following Anne’s death in 1938, Augustus remained in the increasingly shuttered mansion until he died in 1953, surrounded by Flemish tapestries, old master paintings, and silence.

Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation

Obsessively protective of the family legacy, Augustus notoriously refused researchers access to the family crypt beneath St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, reportedly bristling at any suggestion that enslaved people, whom Peter Stuyvesant had owned, might be buried nearby. After his death, the crypt was symbolically sealed in brick and mortar, thereby closing the chapter on the Stuyvesant dynasty in New York City.

A 1953 New York Times report described the funeral as attended by a few distant cousins, a lawyer, and a “ruddy-faced butler dressed in black, weeping into his handkerchief.”

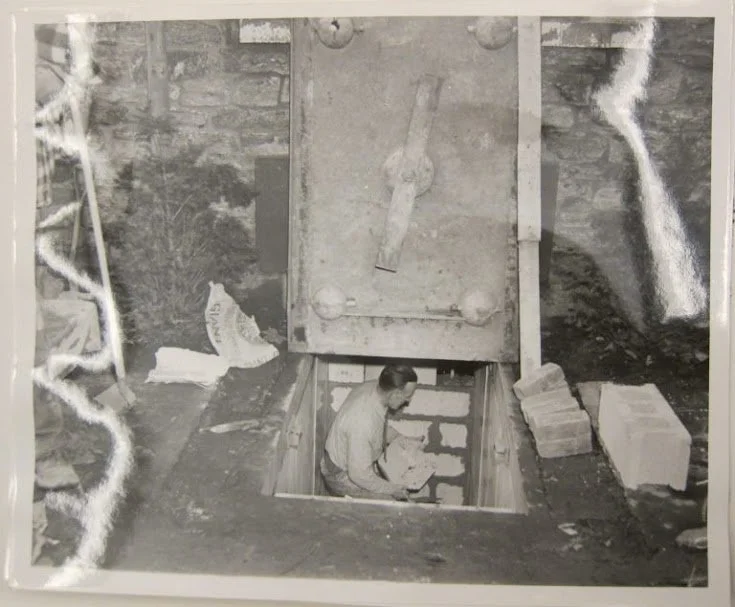

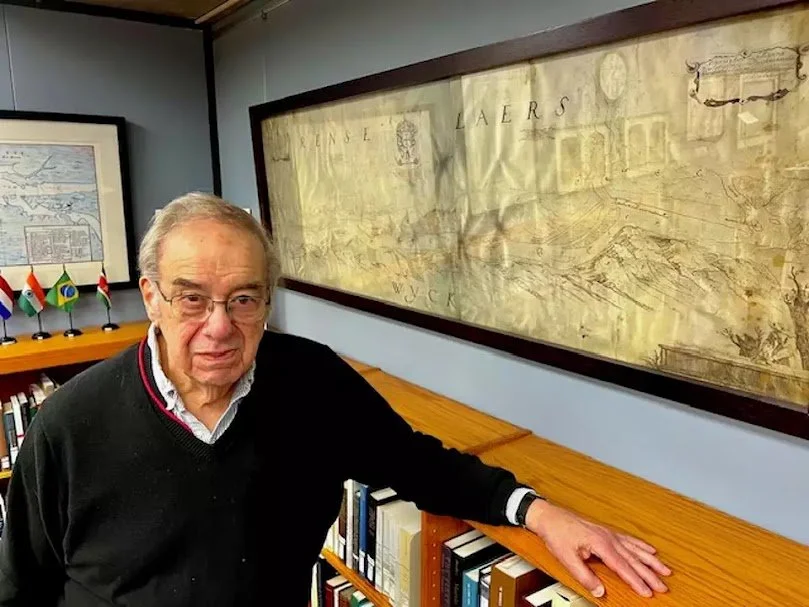

Dr. Charles Gehring at the New Netherland Research Center in 2025, marking his retirement after 50 years of translating 17th-century Dutch records.

Language, Law, and Lost Archives

Despite the British takeover in 1664, Dutch remained a spoken language in New York for over a century. It was common in homes, churches, courts, and newspapers, especially in the Hudson Valley, Brooklyn, and Long Island. Into the early 1800s, some New Yorkers still spoke little or no English.

Much of New Netherland’s original documentation, written in 17th-century Dutch, remained untranslated and ignored until the 1970s, when Dr. Charles Gehring began a decades-long effort to recover and translate it.

Thanks to Dr. Gehring’s work with the New Netherland Institute, we can now read petitions, court cases, contracts, and colonial gossip, and better understand key documents like the 1657 Flushing Remonstrance, an early plea for religious freedom that had long been known but is now more fully appreciated in its original context.

Russell Shorto's acclaimed book, The Island at the Center of the World, powerfully illustrates the significance of Dr. Gehring's translations while weaving together stories that feel like eavesdropping on a cast of relatable and occasionally outrageous characters.

Published in 2004, the book draws extensively from the translated documents to tell the story of New Amsterdam, highlighting its role as a diverse and forward-thinking society that helped lay the foundation for modern New York City. Shorto's work has been pivotal in reshaping the understanding of America's colonial history, and it comes highly recommended by Purefinder New York.

Van Cortlandt House, Bronx (top); Wyckoff House, Brooklyn (bottom)

Today, the Wyckoff House in Brooklyn, the Van Cortlandt House in the Bronx (both open to the public as historic house museums), and fragments of Dutch life across the New York area, remind us that New York’s story didn’t begin with the British. It began with the Dutch, but also with the Lenape and other Indigenous peoples, whose lands and trade networks made the colony possible. The Dutch brought an eye for commerce and a degree of pragmatism, but they entered a world already rich with Native diplomacy and culture.

Left to right: Michael Bloomberg, Princess Máxima, Crown Prince Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands (now King and Queen), and Hillary Clinton

From the 18th century onward, formal Dutch-American relations developed through trade and cultural exchange. In 1782, the Netherlands was one of the first countries to recognize American independence, with John Adams establishing a U.S. embassy in The Hague.

In 2009, then-Prince Willem-Alexander and Princess Máxima, now the King and Queen of the Netherlands, attended Hudson 400 celebrations, commemorating Henry Hudson’s 1609 voyage.

In 2025, as the Netherlands and New York commemorate their shared anniversaries, it’s a good time to remember: this city, noisy and diverse, global and stubbornly local, is still very much Nieuw York.

Explore More with Purefinder New York

Want to experience the Dutch legacy on foot? Check out these Purefinder New York walking tours, which—among many other topics—explore hidden Dutch histories across the city:

Each tour reveals a different aspect of the city's Dutch foundations, with stories that are unexpected, unsettling, and memorable!